Richard Willis senior, was an early settler to Van

Diemen’s Land. He hailed from Kirkoswald, Cumberland, England. His origins were

surprisingly humble if it is true that he was originally a shoemaker by trade. He

married Anne Harper, the daughter of a West Indian colonist in 1800 and the

couple migrated to the colony in 1823 with their eleven children. Based on a

favourable recommendation from the colonial office, considerable assets and independent

income, the well-connected Willis senior was awarded the maximum grant of 2000

acres with an additional reserve of another 1000. He further impressed on his

arrival with a hundred head of pure merino stock. Willis senior named his

property ‘Wanstead’. (1) During

a visit to the island in 1839, Merchant J. J. Macintyre of Sydney described the

Willis homestead as a ‘well finished’ three story mansion adorned with a garden

and a large orchard. (2)

Despite his material success in the colony, from the outset Richard Willis senior appears to have proved himself to be quarrelsome. On 20 January 1826, Willis senior was found guilty on two counts out of three charges of libel against businessman Alexander Charlton. (3) Perhaps, at least at that point, his behaviour should be considered within the context of an embryonic, yet hostile, colonial society. Indeed, one of the witnesses called was fellow settler Andrew Barclay, whose own conduct was questioned by the military officers comprising the jury. (4) In contrast to Willis, Barclay was generally regarded as being a modest, unpretentious man who was well remembered in his community long after his death. But clearly, even Barclay could not completely escape the mire of competing interests, expanding egos and high emotions. (5)

Overtime, Willis senior gained a reputation not just

for being difficult but for also being unjust and even cruel. One example

occurred when he failed to recuse himself from the trial of an absconded

convict David Turner in April 1834. Turner had been assigned as a servant to

his son, Richard Willis junior. (6) Turner had absconded in early March – possibly significantly at the tail end of

peak harvest on the island. (7) He

was subsequently apprehended in early April. (8) Along with another magistrate, Willis senior sentenced Turner to three years

hard labour at Port Arthur despite Turner’s overall favourable record as a

prisoner during the preceding four years. The decision caused an outcry to the

extent that representations were made to Governor Arthur, who in turn mitigated

what was generally regarded as being ‘…such a dreadful and cruel sentence, for

such a trifling offence…’. (9) This

decision was made despite the fact that Arthur is on official record in the

period as stating that any mitigation of a sentence to secondary transportation

‘should be exercised with the greatest discretion.’ (10)

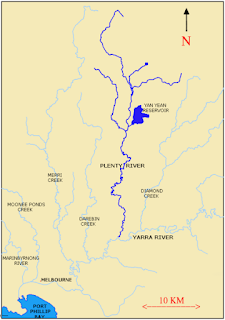

His own family were also victims of Richard Willis

senior’s capricious behaviour. By 1837 Willis senior had driven at least three

of his sons out of his household and into the next colony. That April, James

Lewis Willis along with two brothers transported 650 sheep to Port Phillip. They

established a homestead of their own at the junction of the Yarra and Plenty Rivers.

Over the five-month period James maintained his diary, he made numerous

references to Willis senior, at one point describing him as an ‘…unreasonable

and unfeeling father…’. James laments their reduced circumstances in life and

attributes it directly to his father’s own distracted conduct:

This state of things cannot last long. Some fearful

crisis is at hand. Some impending calamity awaits our family. I dread to

conjecture when my father’s unnatural conduct with have an end – he has driven

out all his sons from his roof and by heaping indignities and unjust reproaches

upon his wife seems either to wish her to follow them, or seek rest in another

world being resolved that in this world she should find none.

Even if this account is exaggerated, it’s likely strong evidence that Willis senior was at least to some degree financially and psychologically abusive to his family. Indeed, James claims to be measured in his appraisal of his father noting that ‘I could say a great deal more. I could explain the cause of this infatuation prompting in his heart hatred towards his family.’ But he does not. His father’s conduct is lastly and concisely described as being ‘unkind and inconsistent’ when a previous promise to lend his brother Edward assistance was not realised. (11)

Although Governor Arthur had made Willis senior a member of the Executive Council and he had gained the favour of his successor Governor Franklin, he was still at war on his departure from the colony; planning to appeal a lost case over a land dispute directly to the colonial office, he and his wife sailed for England in February 1839. Perhaps because Willis senior had burned most of his social bridges, the couple never returned. (12)

- Colin Mallett, 19 January 2024.

Endnotes

(1) P.

R. Eldershaw, ‘Willis, Richard (1777-1855)’, Australian Dictionary of

Biography online, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/willis-richard-2798,

accessed 3 July 2023.

Primary Sources

Secondary Sources

(2) Mitchell

Library: James J. Macintyre - Notes and diary 1839-1840, MLMSS 1721, p 12.

(3) Tasmanian

Archives: Supreme Court (Register’s Office); Minutes of Proceedings, Various

Centres, including Norfolk Island, SC32-1-1 1826, entry 131, https://stors.tas.gov.au/SC32-1-1$init=SC32-1-1P137JPG,

accessed 3 July 2023.

(4) ‘Launceston

News’, Colonial Times and Tasmanian Advertiser, 27 January 1826, p3,

Trove https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/2447063,

accessed 3 July 2023.

(5) Karl R. von Stieglitz, A History of Evandale, Birchalls, Launceston,

1967, pp 17, 20.

(6) ‘Our Correspondent at Norfolk Plains’, The Colonist and Van Diemen’s Land

Commercial and Agricultural Advertiser, 29 April 1834, p 3, Trove https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/201159321,

accessed 3 July 2023.

(7) ‘Absconded’,

Hobart Town Courier, 7 March 1834, p 2, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/4186622,

accessed 3 July 2023.

(8) ‘Apprehended’,

Hobart Town Courier, 11 April 1834, p 2, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/4185580,

accessed on 3 July 2023.

(9) ‘Our

Correspondent at Norfolk Plains’. David Turner’s conduct record (police number

522) was not spotless as he had previously served one week in irons for

insolence and at another time was reprimanded for uttering a falsehood.

Additionally, Turner was suspected of being ‘connected with runaways’

during his flight. Refer to Tasmanian Archives: Convict Department; Assignment

system – male convicts, CON

31-1-43 1803-1843, https://stors.tas.gov.au/CON31-1-43$init=CON31-1-43P19, accessed 7 June 2023. At the very

least the incident indicates there was a growing perception that Willis senior

abused the application of his authority as a magistrate although the sentence

was passed in conjunction with another magistrate: William Gray. This is likely

the William Gray first appointed as magistrate in July 1828. Refer to: Hobart

Town Courier, 12 July 1828, p 1, Trove https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/4221781, accessed 3 July 2023. While Willis

senior is also listed, he was first appointed in 1825. Refer to: Hobart Town Gazette and Van Diemen’s Land

Advertiser, 29 April 1825, p 1, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article1090707,

accessed on 3 July 2023.

(10) Tasmanian Archives: Supreme Court

(Register’s Office); Minutes of Proceedings of the Executive Council, EC4/1 as

quoted in Hamish Maxwell-Stewart, Closing Hell’s Gates the death of a

convict station, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, 2008, pp 263, 290, 293.

This ‘mitigation’ then strongly suggests that at least in this instance there were

genuine grounds for a genuine miscarriage of justice having occurred.

(11) James L. Willis, ‘A Pioneer

Squatter’s Life’, in Michael Cannon and Ian Macfarlane (eds), Historical

Records of Victoria, Foundation Series, Volume Six, The Crown, the Land and the

Squatter 1835-1840, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1991, pp 182-200.

The young Willis’ diary which has been retained by his family to the present

day, remained unpublished until this volume. James L. Willis comes across as a

rather endearing character as much concerned with the wellbeing of his mother

and siblings as himself.

(12) Eldershaw, Biography.

Bibliography

Primary Sources:

Colonial Times and Tasmanian Advertiser

The Colonist and Van Diemen’s Land Commercial and Agricultural Advertiser

Hobart Town Courier

Hobart Town Gazette and Van Diemen’s Land Advertiser

Mitchell Library: James J. Macintyre - Notes and diary 1839-1840, MLMSS 1721.

Tasmanian Archives: Convict Department; Assignment System – male convicts 1803-1843, CON31-1-43.

Tasmanian Archives: Supreme Court (Register’s Office); Minutes of Proceedings, Various Centres, including Norfolk Island, SC32-1-1.

Secondary Sources:

Maxwell-Stewart, Hamish, Closing Hell’s Gates the death of a convict station, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, 2008.

Stieglitz, Karl R., A History of Evandale, Birchalls, Launceston, 1967.

Willis, James L., ‘A Pioneer Squatter’s Life’, in Historical Records of Victoria, Foundation Series, Volume Six, The Crown, the Land and the Squatter 1835-1840, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1991, pp 182-200.

Online Sources:

‘Eldershaw, P. R., Willis, Richard (1777-1855)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography online, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/willis-richard-2798, accessed on 03 July 2023.

Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Main_Page, accessed 03 July 2023.